Growing up in Nova Scotia, I looked forward to my annual summer trip to Prince Edward Island with my cousins and grandparents. One of our favorite stops was always Ripley’s Believe It or Not in Cavendish. I knew curator Robert Ripley was a cartoonist but I had no idea he was so much more than that until very recently.

The Talented Mr. Ripley

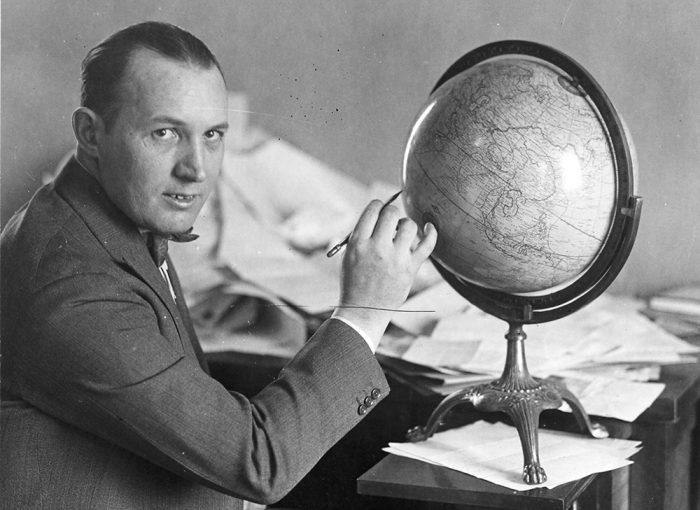

Like all good rags to riches tales, Robert L. Ripley’s story begins with a loner with no obvious future prospects.

LeRoy Ripley was born in 1890 in northern California. The Ripley family struggled to make ends meet and when Ripley’s mother had leftover fabric from sewing jobs, she used it to make clothing for her son. This didn’t make LeRoy popular at school and his stammer and mangled collection of teeth didn’t help. Because of his crooked smile, the young boy kept to himself, instead pouring hours into his favorite hobby—drawing.

Ripley’s hometown of Santa Rosa includes a Chinese neighbourhood. On one of his many solo wandering adventures, Ripley wound up there and quickly fell in love with Chinese culture—an admiration that would stay with him for the rest of his life.

When he sold his first drawing to Life magazine when he was 18 for $8 (about $220 in today’s money), it gave him a glimpse of a possible career. The following year, he packed up and moved to the big city.

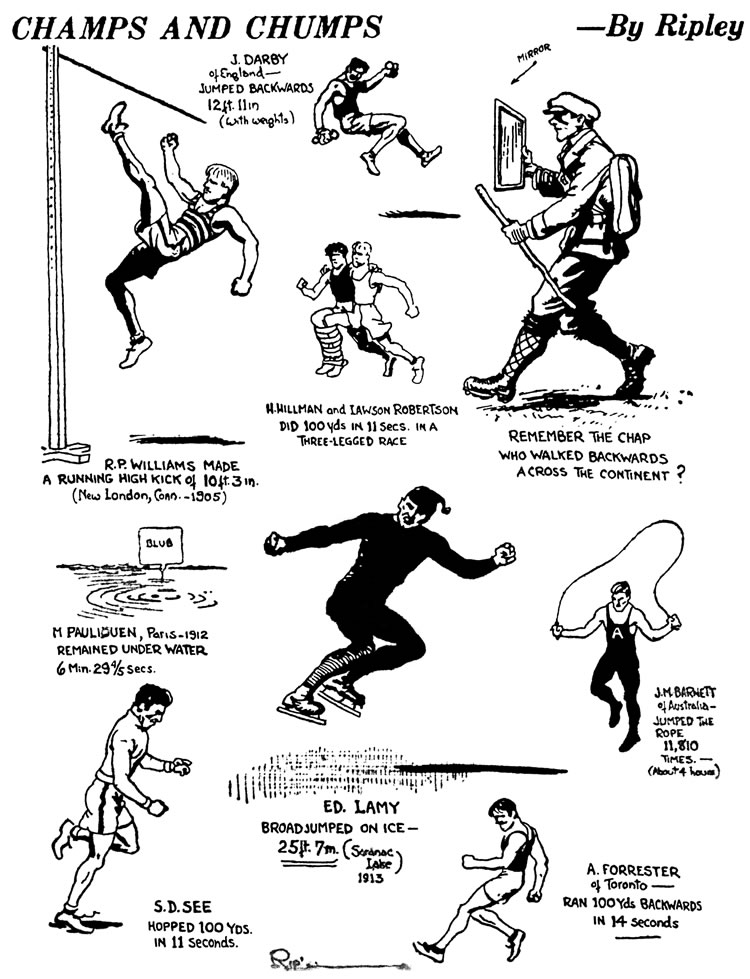

Champs and Chumps

Ripley got a job as a sports cartoonist in San Francisco at The Bulletin , the first of many newspapers he would call home over the course of his newsman career. Since newspaper photography was in its infancy, publishers depended on artists like Ripley to draw athletes in action.

Happy to send money back home to help support his family, Ripley eventually made the move across the country to New York. When Ripley wasn’t sketching up a still from a big sporting event or writing a story to go along with it, he could be found at the New York Athletic Club, playing handball, or knocking back drinks at one of the city’s many prohibition-defying watering holes.

On a slow news day in December 1918 when there wasn’t much to report on in sports news, Ripley (now going by “Robert” or simply “Ripley” instead of “LeRoy”) was struggling to file a cartoon for the next day’s paper. Always fascinated by trivia and factoids, he pulled out his scrapbook of clippings and drew a collection of doodles on the page, each one depicting one of the handful of sports facts. The drawing ran under the heading “Champs and Chumps” and he did a similar cartoon a year later, retitling it “Believe It or Not.”

By the time Ripley landed at The Globe , his cartoons were syndicated in newspapers across the country. He’d developed a love of traveling, had covered the Antwerp Olympics in 1920, and had fallen in and out of love with a Ziegfeld Follies girl.

Ripley was soon given an opportunity that would not only get him away from the drama of his messy divorce, but would also have an incredible impact on the trajectory of his life.

Ripley’s Ramble

The Globe booked Ripley on a four-month around-the-world cruise on the RMS Laconia in 1922—a major writing and cartooning assignment. Ripley would write and draw correspondence for the paper, reporting on the interesting sights, smells, tastes and sounds of Japan, China, the Philippines, Java, Singapore, India, Egypt, Israel, Monaco, France, and Italy. The column, called Ripley’s Ramble ’Round the World , was syndicated in many major American newspapers, their readers fascinated by mysterious parts of the world.

His columns revealed Ripley to be “an everyman,” especially when compared to some of the stuffier travel writers of the day—relatable and entertaining while also learning as he learned. Ripley was an enthusiastic traveler but not without his quirks: he was unwilling to learn any of the language of the countries he was visiting, advising his readers that if visitors speak English

loud enough, the people around them will just figure it out.

He returned to New York a changed man. He was humbled and inspired, his eyes open to the wonders of the world beyond the United States. His affection for Chinese culture deepened while his fascination with Indian religious traditions blossomed.

Ripley and Pearlroth

The late 1920s saw great things coming Ripley’s way. His first book, Ripley’s Believe It or Not! , was released in 1929 by Simon & Schuster. His travels continued, backed by the deep pockets of newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst. Endorsement deals flooded in and speaking engagements kept Ripley busy.

Ripley was one of the few people making a fortune during the Great Depression. Although traveling during this era was out of the question for most Americans, Ripley’s columns and books provided a glimpse at an unfamiliar world many could not afford to visit.

However, most of Ripley’s “discoveries” while abroad were actually found first by Norbert Pearlroth back in New York. Pearlroth, a brilliant researcher who spoke several languages, had been a paid assistant of Ripley’s since 1923. He spent all day at the New York Public Library, scouring shelves for interesting tidbits, these factoids directing Ripley’s travels. Pearlroth continued researching for Ripley’s Believe It or Not until 1975.

Ripley the Entertainer

Warner Brothers Studio produced a series of film shorts in 1930, starring Ripley looking awkward on camera. While calming his nerves by having a drink at hand at all times, Ripley tells the audience of his greatest oddities. His lack of star-style charisma and looks were, ironically, part of his appeal. If this guy could travel the world and become rich and famous, maybe anyone could.

Around the same time, Ripley conquered the radio waves. His massively popular weekly program included Ripley discussing curiosities and recording live from unusual places. Some one these places included the bottom of the Grand Canyon, the sky, a snake pit, and even from under water.

By the middle of the decade, the unconventional cartoonist was now a major celebrity.

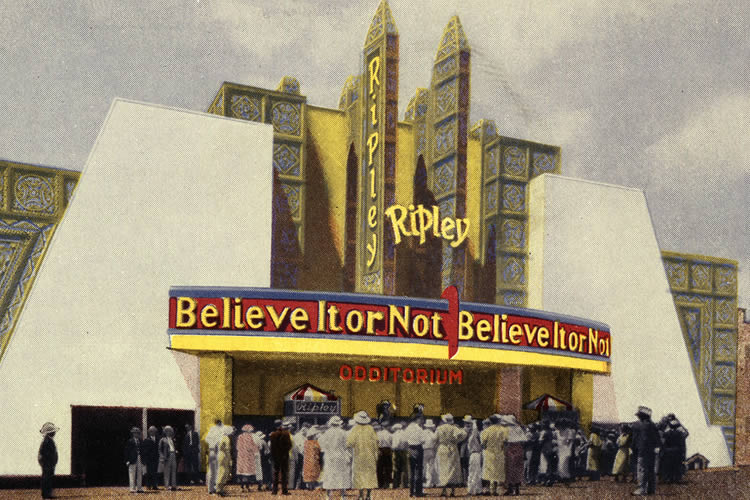

Ripley’s Odditorium

Ripley’s first Odditorium opened at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933. The unusual museum included photos, props, illustrations, statues—physical evidence of the wild wonders featured in his cartoons and on his radio show. The Odditorium also included a live show featuring performers who could do amazing acts as originally seen in his other media. Because of the show’s shocking content, nurses were kept on staff for audience members who fainted.

Ripley’s overseas expeditions ended as World War II made traveling unsafe. His newspaper cartoons soon took on a patriotic angle, featuring incredible feats and interesting factoids from the front.

Ripley’s health declined around this time, but it didn’t stop him from planning his last big adventure to Asia. However, the China he found was not the land he remembered—war-torn, broken, and in disarray. It was a much more solemn trip than any he’d taken before.

The Death of a Legend

The Ripley empire was in its newest phase in 1949: a hit television show. The 58-year-old Ripley told viewers about a fantastical and amazing discovery he’d found while on his travels. He was still uncomfortable in front of a camera but viewers loyally tuned in every week.

While filming an episode in May, Ripley had a heart attack and died a few days later. Robert L. Ripley was buried in Santa Rosa, California.

Having visited 201 countries during his lifetime, the cartoonist, traveler, writer, entertainer, and curator of the world’s weird and unusual was also one of the most traveled individuals of his day.

Since 1933, over 100 million people have visited the various Ripley’s Believe It or Not attractions around the world.

- A Curious Man: The Strange & Brilliant Life of Robert “Believe It or Not” Ripley by Neal

Thompson (2013) - Ripley: Believe It or Not – PBS (May 2017)